We were recently story wrangling at Haulin’ Colin’s here in Seattle. Read his story here. The following text is from the post-interview hang out/beer drinking/storytelling session. As Colin and I finished talking, his friend Brad joined us, as did my husband Daniel, and our friend Fisher, who had introduced me to Colin. I saw as I read this transcript that the five of us were a self-organizing group: more emergent than planned, more internally created than externally created.

You can read this just for the fun of it–the humor, epic storytelling, and teasing–or, if you’re a research geek like me, read it looking for self-organizing group indicators, asking yourself what qualities you see in this group, what each person taught and learned, and which groups in your own life have similar qualities.

Brad: How’s it going?

Colin: Good.

Brad: Sorry, I’m interrupting your.

Lori: You’re not. I already asked him my last question. [Colin laughs]

Brad: Well I don’t have any questions. [We all laugh]

Brad: I was thinking about actually just trying to mooch another beer.

Lori: Oh. Go ahead!

Colin: I think that’s totally acceptable.

Brad: It’s keeping morale up.

Someone (Fisher?): As long as morale’s up, take two.

Brad: Morale is high. [He opens a beer] I can continue working!

Colin: Brad’s been rebuilding the engine in his pickup truck. It’s a long project.

Brad: It’s extremely time consuming. Like two years.

Colin: No!

Brad: Somebody said that to me today and I was like, “What?! Really? Has it been that long?”

Colin: I don’t think it’s been that long. But our shop mate, Michael, is just this fountain of information. Just like every time you have some question, like some really technical thing, about rebuilding an engine. You know, I’ve never seen him do that, but I don’t know how he knows all this stuff. But he’ll just be like “Oh, yeah. That just works like such and such.”

Brad: Yeah.

Colin: “It’s easy.”

Daniel: That sounds like my brother. If he’s read it on the Internet, he feels like he has the experience. [Colin laughs.]

Colin: Right!

Daniel: So he has all this knowledge and you have no idea if it actually works or not. But, you know, it’s right a lot!

Brad: Michael is reliable.

Colin: Yeah.

Brad: Except that it’s a diesel, so he’s a little less knowledgeable, which is shocking given his baseline level of knowledge. It’s pretty shocking [that he’s so knowledgeable] given that it’s outside his area of expertise.

Lori: That’s like Daniel with computers. I swear to God that he can walk into a room and the computer decides to fix itself.

Colin: Right.

Brad: Yeah, Nas—ah, Michael—has been described that way, with cars, actually. That he can just get it running. And maybe, if he leaves, it’ll stop. [We all laugh.]

Brad: And if he comes back, it starts running again.

Colin: He always pulls that kind of thing. Where he’s “Aw, maybe you should just, I don’t know, tweak this thing a little bit.” And poof, it works.

Lori: Well, now that I know you have an event in December. Is it a public thing?

Colin: Oh yeah.

Lori: Very cool.

Daniel: We did that one year. Don’t you remember we were back over by Stellar?

Lori: Oh. But we didn’t make it to this building.

Daniel: But we did that.

Lori: We did the art walk.

Colin: Yeah. Georgetown has an art walk the second Saturday of every month. Technically this building is a part of it even though most of the stuff happens over on Airport Way. And it’s hard to get people to come all the way over here. So the once a year, really big event.

Lori: They have an open-house in December.

Colin: Yeah. It usually coincides with the regular. It’s on the second Saturday, so it coincides with the regular art walk. The art attack, as they call it in Georgetown.

Lori: Yeah.

Colin: But it’s a much bigger event. More widely publicized.

Colin: But it’s a much bigger event. More widely publicized.

Lori: We’ll definitely have to come and see it, because I’d love to see all the rest of the spaces.

Colin: Yeah, there are a lot of people. You know, Sam—who’s the manager here—who’s buying the building and fixing it up, you know, this used to be a big manufacturing facility until it got subdivided into all these little spaces—he is also managing InScape, the old immigration building. You know where that is? How Airport Way kind of starts by splitting off onto 4th Avenue, and going diagonally over? There’s a big old government building there, across the street from the Shell station. The old immigration building. And it has now been subdivided into artist spaces too.

Lori: It’s called InScape?

Colin: It’s like three times the size of this building.

Lori: Huh.

Colin: And it’s full of people doing stuff.

Lori: Wow.

Colin: It’s less, ah, there aren’t as many metal working and woodworking shops. A lot of painters and artists.

Fisher: Less industrial art.

Colin: Yeah, less industrial. There’s one shop that makes bicycle frames in there and some stuff in the basement.

Lori: Yeah. From my perspective, I don’t care what exactly people are doing. What I’m looking for is people who feel how you feel about this space. People who’d say “I LOVE this space.”

Colin: Yeah.

Lori: In part, just because I feel like, ah, in a lot of ways, like you’re my people. I’m trying to create a community coworking space that people feel that way about. So I need to hear from a lot of different people to learn how to make a space like that. I also just love spending time with people who have actually done it: actually created spaces that they love. Because it’s not always easy.

Colin: I mean, it did just kinda happen. [We laugh]

Colin: It just kind of became a larger and larger part of my life. Now, it’s like what I do all the time.

Lori: Very cool. Well that’s all my questions. Thank you so much.

Colin: Yeah.

Lori: For showing us your space. And your time.

Fisher: How many trailers are you shipping out of state now?

Colin: I have shipped one trailer out of state.

Fisher: I was reading about. There’s some guy out of state who bought it. Where is it?

Colin: New Jersey. But there is definitely one of my trailers in the Bay Area [San Francisco] because someone in Seattle bought one and then I think they rode to the Bay Area and then sold it second hand to someone else. So I’ve heard from that guy.

Fisher: Ok.

Colin: And because Dave bought that batch of 20 and was just distributing them, there’s 20 of them out there! [We all laugh.]

Colin: And I don’t know all the people anymore! They’re on the second-hand market now. It’s crazy.

Lori: Did you have any more questions? [to Fisher]

Fisher: Oh, I do, but just about other stuff.

Lori: But not for this? You sure?

Fisher: I’m just very curious about. Are there structural things that would make your work feel more effective?

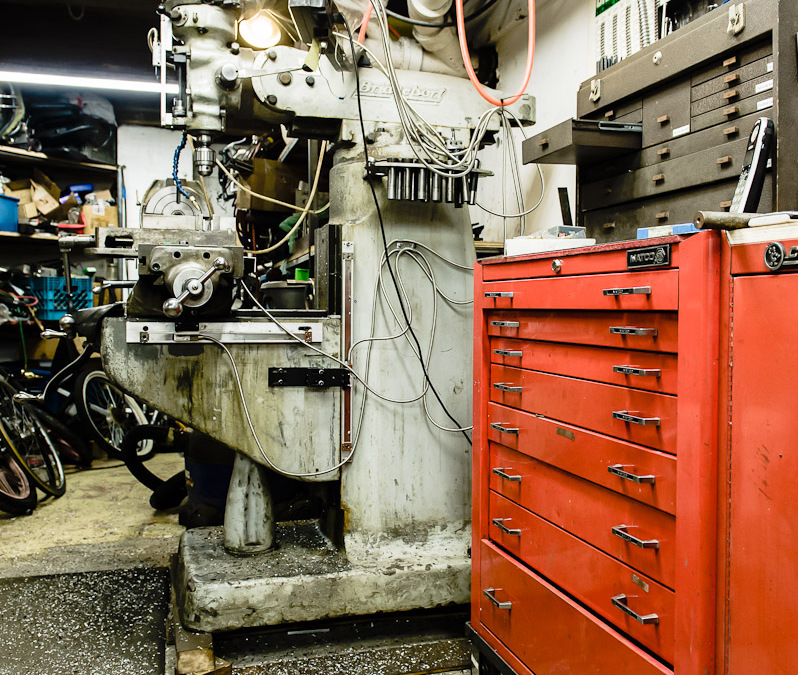

Colin: Ah [he pauses], well, yeah, I struggle with that. I struggle with being efficient and staying on track and charging enough. [Fisher laughs] We have pretty low overhead. A lot of times I have to quote people prices where I think to myself “God, I would never pay that much for that.” But it’s like, you know, the shop rate. Here we have a hundred thousand dollars worth of tools, or something, I don’t know. And the shop rate is 60 dollars an hour. Most of that goes back into the shop. Goes to pay for tools, repairs, the compressed gas, the welding wire, sanding discs, whatever.

Fisher: Yeah.

Colin: I don’t ever really make any profit because I’m just like “Well, now I can buy another tool!” [We all laugh.]

Colin: So yeah, like structure, being efficient, I [he pauses a long time]. I don’t know. It’s hard. We usually have a whole bunch of different projects going at once. And it’s less efficient when I’m jumping from one project to another. It’s better when I set aside X amount of time, or a couple of days, to work on one thing. But sometimes it just works out like that. I have to order parts and I’m waiting on parts for one thing. And you know what? I probably spend an hour or two. I probably spend at least two hours a day writing emails and talking on the phone and ordering parts. It’s like a pretty big.

Fisher: Administrative part.

Colin: Yeah. Feel like I need a secretary.

Brad: But they’re like $80 an hour now. [We all laugh.]

Colin: Yeah. I just get emails all the time. People who want custom things. Then we have to imagine a design. Talk about how much it would cost. Sometimes they follow through and it becomes a project and I actually make money. Sometimes not.

Fisher: So you’re not charging a design consulting fee?

Colin: No. I mean, if there’s a lot of design work, technically we have a $30 an hour design time rate. But if someone just emails me and they’re like “Hey, I have this cool idea! For a trailer that has such and such.” Then I’m like “Ok.” I think about it while I’m riding my bike home or whatever. And I’ll be like “Ok, that’s roughly going to cost such and such.” But I’m always quoting out jobs beforehand. And then they take longer then they think they’re going to take. Classic. Happens all the time. No matter how many times I do it. Just takes longer. So jobs. This year we’ve gotten more contract machining jobs, where some other machine shop needs some work done, and they sub-contract it out to us. And we just charge hourly: “Ok, it took X amount of hours.” And machine shops don’t blink an eye at $60 an hour. They’re like great, no problem. But ah people. People who.

Daniel: People who want a $200 trailer.

Colin: Yeah, right.

Daniel: Say “Can you get that done in 3½ hours?”

Colin: Right.

Lori: That’s what Nils and Grant do! Their friends call them up and are like “I need a table and I have $300 dollars.” [Colin laughs] “Whatever amount of time it takes you to make a table for $300, please do that.” [Lori laughs]

Colin: Yeah. It’s interesting. I like making weird custom stuff for people who want to do it. But sometimes its just not realistic. I probably spend too much time messing around on the Internet. But I can justify that. That’s my break time. If I’m here for 10 or 12 hours, I get to spend a couple of hours doing stupid shit on the Internet. Looking at funny pictures or something.

Lori: Yeah.

Fisher: Is there anything you need? Just like, stuff that you need?

Colin: Well, we always need more tools. [Colin and Fisher laugh.]

We’re always buying more tools. We have a line of things, like when we all have enough money. We split everything three ways. So when we all have enough money we’re going to buy a new tool post for the metal lathe. That’s like $500. Then we’re going to buy a new set of bearings for the other metal lathe there that’s all taken apart. They’re super-precision bearings because it’s a precision tool, so that’s like $300 for a pair of bearings for that.

We’re always buying more tools. We have a line of things, like when we all have enough money. We split everything three ways. So when we all have enough money we’re going to buy a new tool post for the metal lathe. That’s like $500. Then we’re going to buy a new set of bearings for the other metal lathe there that’s all taken apart. They’re super-precision bearings because it’s a precision tool, so that’s like $300 for a pair of bearings for that.

Lori: That’s a really good question since we’re basically publishing the entire interview and building photos and video into them. Anybody who likes your story enough, could hit that question and think to themselves “Well, I have $300. I could send it to them!” [Colin belly laughs at the idea of someone just sending them money.]

Fisher: Well there’s that and then there’s also. Ultimately what Sean and I want to do is put together some sort of fund. Even if it starts out at a thousand dollars. And then when a [bike-related] small business owner needs $500, they can get a no-cost loan.

Colin: Oh, yeah. Cool.

Fisher: And even if we never get the money back. [Colin belly laughs again.]

Fisher: It’s not a huge deal, you know.

Lori: Oh! It’d be like bike Kiva.

Fisher: Yeah, that’s the vision for it.

Daniel: Which has an amazingly high pay-back rate, over 90%, better than most banks.

Colin: What is it?

Lori: Kiva.org.

Daniel: It’s for microloans. So you get online, put money into their bank account, and then you pick who you want to loan the money to and how much. And where. Guatamala. Nigeria. Whatever. And then you can follow along and see the loan get paid back.

Colin: Cool.

Lori: Teeny, tiny business loans.

Daniel: Once the loan’s paid back, you can loan the money out again. Pays like 1.6% interest, or something like that.

Lori: It’s literally sometimes like people who need just $25 to start their business and it would feed their family for the rest of their lives. It’s often just tiny amounts of money.

Colin: That’s cool.

Fisher: To us.

Lori: Yes, [tiny amounts of money] to us. [Colin laughs.]

Fisher: There’s another one: Vittana, which is local here in town. They do it for education loans in Latin, Central, and South America.

Colin: We’ve talked about getting loans sometimes, but always shied away from it.

Fisher: Yes?

Colin: Because it’s nice to not be in debt. And as long as we don’t need to do that, it’s better. It always gets really busy in the summer and slow in the winter. Always pulling out of the winter it feels like we’re struggling a little bit. Now. This time of year it’s great. Lots of work.

Fisher: Do you make Pedi’s? Pedicabs?

Colin: I have made two pedicabs. And I’ve worked on a few [more], yeah. Those things get abused. They get heavily used. Really, I don’t know of any shop better than us to work on them because we have this crossover into heavier duty, moped and motorcycle stuff, and we can take advantage of that. But even so, I’ve seen those things come back over and over again. You know, broken frames, broken wheels, they just need heavier duty parts.

Fisher: Yeah.

Daniel: So when you run into an engineering block—you start fabricating and its not working out—how do you work through that?

Colin: Um, I mean, none of us are engineers. [Colin laughs] I have a pretty good sense of how stuff works, you know, what size of metal to use for what thing just from experience, but that’s kind of what I wish I’d done in college now. Like if I had a mechanical engineering degree. God, that would make a huge difference. But, we basically, the three of us have a lot of experience and we’ll just bounce ideas off of each other if we’re having trouble, designing something or figuring out how it works. I have a couple of other friends that I can call. People who do have an engineering degree, or a math degree, or something that could come in handy—who I can call to get advice.

Lori: The small business within a big building of small businesses probably comes in handy.

Colin: Yeah, although we are, our shop. I mean. There’s lots of experience, and that’s good to call upon. But no other shop in the building is making stuff at the same level of, like, precision and engineering as we are. Like, the blacksmiths will make beautiful, ornate railings, staircases, whatever. But they’re hammering giant pieces of solid bar into shapes.

Lori: Nobody has to ride them around town! [laughs] Colin:

Making things with moving parts. We’re already more technically advanced than the other shops here. People come to us with their broken power tools, and stuff like that. We fix that stuff.

Lori: Yeah. That’s it for me. You guys, anything else?

Fisher: I’m curious, what you—over 1, 3, 5 years—do you want the trailers to be in retail stores or—is this part a business to you or?

Colin: The bike trailers are the thing that I started trying to make a business out of. But overall they’re a small part of the work that I do. Maybe 20% of the work that I do. Every day I get little jobs—stuff like this—broken frames, people need brazons, cargo bikes.

Fisher: Is it almost all bike work?

It’s a more reliable way to make money—to have products—but it’s more fun to do custom stuff. Yeah.

Colin: Yeah, it’s almost all bike work. Ninty percent bike stuff. But yeah, the trailers. It’s cool to have a product that I make a lot of because I can really refine the process and I don’t have to take the time to do design work and I know how long it takes me and how much to charge. So that’s good, but I’m not really married to the idea of turning the trailers into more of a production thing. Because it’s ok. I like it. It’s a thing I know how to do now, so I get requests for custom trailers and I’m happy to be doing that, but I don’t see myself pursuing any kind of, like, mass marketing or wholesaling them to shops or anything. It’s a more reliable way to make money—to have products—but it’s more fun to do custom stuff. Yeah.

Fisher: Cool.

Lori: Thank you. [to Fisher and Colin and Daniel–Brad had left]

Fisher: Thank you. [to Lori and Colin]

Fisher: How did you get that big machine in here?

Daniel: That occurred to me as I looked at the lathe.

Colin: I think the lathe is about 2500 pounds. It was actually an epic journey from that lathe’s old home. Ok, this happened because I used to work at Hardwicks, ancient hardware store, lots of good stuff. The owner of Hardwicks, one of the owners had bought a bunch of stuff from a lady who was cleaning out her dad’s basement. He was a contract machinist for Boeing. Had just turned the basement of his house into a machine shop, basically. It was this neat old house in Burien, on the water front, just basically walk out the backdoor and there’s a little path this [a foot] wide and then a rock retaining wall down to the beach. At high tide, the water’s halfway up the retaining wall.

So he told me about this metal lathe there and he’s like “There’s no way I’m trying to get that thing out of there. Go look at it if you want.” So I went and looked. He had moved the thing in in the 70s or 80s on a barge. He got a barge to come over to the house on high tide.

[Lori laughs]

And they used a crane to put it into the house. And walls had been built.

[Fisher laughs]

We were just like “Wow.” But, his daughter wanted to sell the house and is like “How are we going to get rid of this thing?”

Lori: Yeah.

Colin: So we got an amazing deal on it. It was a thousand dollars but that’s cheap for that, with a lot of accessories. Then we had to devise this whole plan. I welded up a custom cart with big casters. Then we had to disassemble part of two different walls. And then, instead of doing it high tide on a barge, we got there at low tide and drove our friend’s flat-bed truck down a boat ramp onto the beach and around. And we used a hydraulic engine hoist to lift the lathe up onto this cart, rolled it through this doorway, and then built a ramp that went down over the retaining wall and into the bed of the flat-bed truck. Drilled a hole in the concrete floor of the basement and put in a eye bolt and used a come-along and a chain to let this thing down the ramp slowly into the truck.

Lori: Oh my gosh.

Colin: And then, we got it here and used another crane to get it off the truck and rolled it into here and then used the hoist again to get it off. It was quite the process.

Daniel: My dad has a welding table, probably about half the size of this table but probably two inches think.

Colin: Two inches thick? That’s a lot.

Daniel: So same sort of thing. He lives in east Texas and needed a welding table. So he’s checking Craigslist and some guys dad had died.

Colin: Right.

Daniel: The guy didn’t even know. He’s like this 32-year-old kid, lived in New York City, was some kind of investment banker, and was home just trying to get rid of the stuff out of his dad’s house. My dad drove 50 or so miles up, walked in, and was like.

Colin: “Wow. That’s a big chunk of steel!” [Fisher belly laughs]

Daniel: And he’s like, alright, so what do you want for that? What do you want for that? So my dad looks through a few things. And the guy’s like “So, how do we get it out of here?” And my dad’s like “I don’t know how.

Colin: That’s up to you! [laughs]

Daniel: So my dad and his buddy go back. My dad owns two pretty good sized John Deere tractors. So they drove in with the tractor as far as they could go and hooked it. Lifted it up far enough so they could get some wheels under it. Pulled it out. Lifted it up. Dropped it on the flatbed with the tractor. But yeah. Then he parked it. He was originally going to put it up by the house but he was like “Nah” and bolted it into the garage,ah, barn. And was like “Yeah, so if I have to move it again the tractor is just right there.”

[Everyone laughs]

It’s not like you’re going to just pick it up.

Colin: Yeah, it’s weird moving things. Like, you couldn’t possibly get enough people around that to actually lift it. It’s machines only at that point. But we had the help of Steve, who runs Burning Specialities, which is in the same building here. They cut out those big rounds [under the feet of the machine to raise it higher]. He’s used to moving big slabs of steel. He’s good at that sort of thing. He’s the one with the flat-bed truck. It’s good to have him around.

Daniel: Like with my darkroom. The guy who owns Yuen Lui Studios, a portrait studio up and down the West coast, is named Yuen Lui. He decided dark rooms are dead, so he’s like, “You want it, its yours.” So I went down and bought cameras and sinks and trays.

Colin: Wow.

Lori: Um, yeah. Like a 15-foot-long sink.

Colin: Wow.

Daniel: He’s like “Just get it out of here.” We negotiated a little bit. But same kind of thing: I just couldn’t pass up the price.

Colin: Right.

Daniel: So his assistant came in and said, “Ah, so you do know that there’s no way that’s leaving the building, right? And I’m like “What do you mean?” And he says “The first room built in here was Yuen’s darkroom and every wall was built up after that. [Fisher laughs.] We’ve tried to take it out. Twice.”

Colin: Oooh.

Daniel: I’m like “I’ll get it out!” [Lori laughs] We had to cut one of the braces in half. And the metal sink, with enough flex in it, we actually just flexed it around the corner.

Colin: Wow.

Daniel: But the first couple of tries it was, ah. I had my hand between it and the wall because I was like “I’ll take the hand damage vs. the wall.” [Fisher laughs]

Colin: But you got it out?

Daniel: We got it out. But I had to cut the stand in half.

Lori: Then he brought it home and his wife was like “You’re going to put THAT in our house?”[Colin laughs] It’s a 15-foot sink!”

Daniel: I put some walls around it, it’s fine! [Colin laughs]

Lori: That’s what the basement’s for! [laughs]

Daniel: It’s happy in the darkroom. Ceilings only this tall in the rest of the basement but.

Lori: It’d be a great studio workspace down there for me, but not for him. There are places where the ceiling.

Daniel: I actually knocked myself out one time.

Lori: Yeah.

Colin: Wow. Knocked yourself out.

Daniel: Yep, I turned and bam! Out! Then stumbled around.

Lori: He only did that once and hasn’t done it since.

Daniel: It left a mark. [Lori and Daniel laugh]

Colin: Yeah. Even going down the hallway here. You have to duck just a little bit to get under those beams.

Lori: Our house was built in 1908.And he’s got. Just to go from the first to the second floor up the stairs there’s a spot he has to duck.

Daniel: Yeah. We’d been in the house for about 8 years and she finally goes “You really do have to duck to go under that.” And I’m like “Yeah, for 8 years now!” [the guys laugh]

Lori: I hadn’t noticed for the first 8 years we were in the house.

Colin: You get used to it though. It’s like part of your stride. Your head goes down just a little.

Lori: Not one of those things I’ve ever had to worry about!

****

Photo credits: The first, slightly blurry photograph is mine. All the awesome photos are Daniel’s.

Absolutely awesome from all perspectives. I am sorting out the self-organizing part still, but it is forming in my mind. I enjoyed the conversations; half finished sentences and the fact that you just noticed that Daniel has to duck his head! Keep collecting, keep collecting.

Great comment, Cathy. I am in full agreement. The discussions are organic. Wow! This is a new term “organic discussions”. I bit Lori will use it. I wonder if Lori did any editing to it. I believe enriching the text with more sketches, besides the photos, will help in increasing the pleasure of reading this great post.

Hi Ali! Yes, organic discussions is a great term! What does “organic discussion” mean to you? I think it means from within, from the heart, from the true self, with individual fears set aside for a moment. Perhaps with awareness that the group itself brings this forth in you, which brings forth deep gratitude to the group. Hmm. Still thinking about it.

The only editing I do to the stories as I transcribe them from the audio tapes is to make as many non-verbals visible as possible (like laughter, or speaking the same words at the same time). Because I believe these groups are most powerful not in what they say through words, but in what they demonstrate about us as human beings (basically, everything I just said to Cathy). 🙂

Hi Lori,

Organic produce refer to Organic farming works in harmony with nature rather than against it. No synthetic chemicals or pollutants are used.

So, our discussions here: like you said they are natural and not fabricated or beautified with “cosmetic words”. Wow! This is an organic expression as the term cosmetic words just emerged. No beautifying words to color our discussions and give it a cheating appearance. It is natural and comes with spontaneity.

I better stop here before a new expression pops up

Ali, thank you for being in my life. Your ideas and care and humor make me so happy.

Hey Cathy, hope you’re feeling better!! Here are some self-org group indicators I see: collective laughter, collective reflection, the word “Wow”, finishing each other’s sentences, all members being leaders at different times, all members teaching and learning, reminiscing, people comfortable enough to ask questions and getting their own questions answered, energy increasing, kind self-teasing, people building on each other and weaving their experiences together without even thinking about it, people finding strength and comfort in diversity, and multigenerational learning. Three decades were represented–people in their 20s, 30s, and 40s. And if you count the people who commented on this post so far, like I do, then several additional decades are represented. 🙂 yea!

Great article and follow-up session (I’d have said “bull session,” but Lori was there). I’m Colin’s loving and proud grandfather. It’s so “cool” to have had a grandfather who was into bicycle building and now a grandson doing such similar work. When Colin expressed a wish that he’d earned a mechanical engineering degree, he failed to mention the ancient handbook on machining and related work he’d learned so much from, beginning several years ago. It was published in 1925, the year of my birth, and Colin somehow managed to buy a brand new copy. I had a year of mechanical engineering myself at Stevens Institute of Technology–no family connection–on the waterfront in Hoboken, NJ, then did 2-!/2 years in the Army Air Corps, ending up working on Boeing B-29 Superfortress heavy bomber “computers” near the end of WWII. After military service, I eventually earned a Ph.D. in psychology and spent 35 years as a professor at San Diego State University. Enough about me, now let’s talk about my hair–what little there is left of it.

Hello Russ, it’s so very nice to meet you. I’m touched that you took the time to comment here. Thank you so much for the family history! In 3 years of blogging, this is my all-time favorite comment.

It spoke volumes about your family that the first stop on Colin’s tour of his shop was the photo of his great, great grandfather, which he said you gave him. It colored everything else that happened. He lit up when he spoke of it, and I’m so glad that Daniel got some photos of him in that state! Your comment makes me think that a question about family history should be included in our list of questions for the Different Office web site. I’ve already done the next two interviews (Martina of Swift Industries and Niki of Mobius Cycles), but in the interviews after that, I’m going to add a question. See if I can’t pull great histories like yours up into the interview itself.

We’re always on the look out for self-created, soul-satisfying work spaces, so if you can think of any to share, I’m all ears! I certainly wouldn’t mind a trip to sunny San Diego, especially come winter here. 😉

Thanks for giving Colin to Seattle. We’re so lucky to have him!

Lori

hi Russ and Lori,

Both of you stirred my emotions. Great writings as I see words radiating warmth, respect and genuine respect.

Talking about space, 20X20 feet may accommodate 100 people like you; the same space would not be enough to house two people who have dimmed hearts to each other. (Dimmed hearts!!!!). I feel the space is an issue; the size of which depends on the prevailing feelings.

Yes, it feels like the happier you are with one another (and yourself), the less physical space you crave on a day-to-day basis. I’ve found this to be true in my own life. First one housemate, then two, then three, and now four. Today five humans plus 2 dogs and 3 cats live in our space. And now we’re inviting community members in for coworking two days/week.

Makes me sad for so many people in the U.S. The need for ever bigger spaces and bigger property to get farther away from people you don’t like or trust must feel terrible. I read somewhere this summer that most Americans today live in 4 to 5 times the space their grandparents did.

Well, Lori then I suggest a topic for you to write about

Community and space.